- / Work/

Scaffold

On this page

Reflections on Scaffold after three years (2020) #

Sam Durant, September 2020

It has been three years since my public artwork Scaffold (2012) was protested by Dakota activists and their supporters and then dismantled at the Minneapolis Sculpture Garden of the Walker Art Center. These events are regularly mentioned when the Walker Art Center is in the news, often regardless of Scaffold’s relevance to the story. Frustratingly for me, Scaffold is usually mischaracterized or misinterpreted, particularly in the art press. I realize it is past time to share my perspective on what happened three years ago. I offer my reflections here with self-searching honesty, in the hope that they will elicit good faith responses and encourage more thoughtful, nuanced and factual reporting. The text will cover some of the complex and intersecting issues at stake (personal, artistic, legal, ethical, historical and institutional) and the ways that Scaffold continues to be a lightning rod for the storm that constitutes the cultural moment of our fraught settler-colonial country…

Artist Statement Regarding Scaffold at the Walker Art Center (2017) #

Sam Durant, 5/29/2017

Let me begin by describing the sculpture that has become the focus of protest in recent days as I envisioned it when it was first exhibited in 2012 in Europe at The Hague, Netherlands; Jupiter Artland, Edinburgh, Scotland; and dOCUMENTA (13), Kassel, Germany.

This wood and steel sculpture is a composite of the representations of seven historical gallows that were used in US state-sanctioned executions by hanging between 1859 and 2006. Of the seven gallows depicted in the work, one in particular recalls the design of the gallows of the execution of the Dakota 38 in Mankato, Minnesota in 1862. The Mankato Massacre represents the largest mass execution in the history of the United States, in which 38 Dakota men were executed by order of President Lincoln in the same week that the Emancipation Proclamation was signed. Six other scaffolds comprise the structure, which include those used to execute abolitionist John Brown (1859); the Lincoln Conspirators (1865), which included the first woman executed in US history; the Haymarket Martyrs (1886), which followed a labor uprising and bombing in Chicago; Rainey Bethea (1936), the last legally conducted public execution in US history; Billy Bailey (1996), the last execution by hanging (not public) in the US; and Saddam Hussein (2006), for war crimes at a joint Iraqi/US facility.

Scaffold opens the difficult histories of the racial dimension of the criminal justice system in the United States, ranging from lynchings to mass incarceration to capital punishment. In bringing these troubled and complex histories of national importance to the fore, it was my intention not to cause pain or suffering, but to speak against the continued marginalization of these stories and peoples, and to build awareness around their significance.

Scaffold seeks to address the contemporary relevance and resonance of these narratives today, especially at a time of continued institutionalized racism, and the ongoing dehumanization and intimidation of people of color. Scaffold is neither memorial nor monument, and stands against prevailing ideas and normative history. It warns against forgetting the past. In doing so, my hope for Scaffold is to offer a platform for open dialogue and exchange, a place to question not only our past, but the future we form together.

I made Scaffold as a learning space for people like me, white people who have not suffered the effects of a white supremacist society and who may not consciously know that it exists. It has been my belief that white artists need to address issues of white supremacy and its institutional manifestations. Whites created the concept of race and have used it to maintain dominance for centuries, whites must be involved in its dismantling. However, your protests have shown me that I made a grave miscalculation in how my work can be received by those in a particular community. In focusing on my position as a white artist making work for that audience I failed to understand what the inclusion of the Dakota 38 in the sculpture could mean for Dakota people. I offer my deepest apologies for my thoughtlessness. I should have reached out to the Dakota community the moment I knew that the sculpture would be exhibited at the Walker Art Center in proximity to Mankato.

My work was created with the idea of creating a zone of discomfort for whites, your protests have now created a zone of discomfort for me. In my attempt to raise awareness I have learned something profound and I thank you for that. Can this be a learning experience for all of us, the Walker, other institutions and artists and larger society? I look forward to meeting the Dakota Elders on Wednesday in Minneapolis, and am open and ready to work together.

Original Artist Statement for Scaffold (2012) #

The opposite of love is not hate, but indifference. Indifference creates evil. Hatred is evil itself. Indifference is what allows evil to be strong, what gives it power.

Elie Wiesel

Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly. I can never be what I ought to be until you are what you ought to be. This is the interrelated structure of reality.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Because of the intricacy and complexity of this structure, it may not be immediately apparent as to exactly what its origins are or how it is to be used; while children use it as a play structure, adults, perhaps attracted by its architectural novelty can slowly discover its origins and meaning. While some might see a resemblance to constructions in an adventure playground from the 1970’s, the sculpture is actually made up of a combination of reconstructed gallows (or scaffolds as they were once called) that were used in executions of significance throughout U.S. history. Through this formal uncertainty there is an attempt to signify both the free play of childhood and the ultimate form of control, capital punishment. These seemingly oppositional tracks have come together in the United States in the last decade, resulting in what is known as “the School to Prison Pipeline.″1

The reconstructed gallows are built on top of and into each other to form a single, integrated unit. The different gallows are arranged around a center point and stacked one on top of the other, so that the deck of the most recent gallows forms the bottom layer with each successive layer built up chronologically. The viewer can explore the structural aspects underneath the deck while children have ready-made climbing frames. Visitors can then access the platform via two staircases where factual information about the project can be found.

The gallows used in the sculpture represent a range of executions, some nearly iconic, beginning with John Brown in 1859 and culminating in the scaffold used in Saddam Hussein’s hanging in 2006.2 There is no intention of directly equating the victims of the various executions or of making equivalencies between the activities that led to their deaths. The only consistency implied in the project is that they are all State sanctioned executions. Some of the other gallows represented include the last public hanging in the U.S. in 1936 attended by tens of thousands as well as the 1996 execution that became the last death by hanging in the United States.

The United States has a long history of executing prisoners dating back to its founding settlements and unlike Europe the death penalty is still in practice today. Hamida Djandoubi was the last person put to death in Europe before the continental moratorium on executions took effect in 1977. Perhaps ironically, 1977 was also the year that saw the United States execute Gary Gilmore, the first execution after a brief moratorium period.3 Since its 1977 re-instatement capital punishment has become a popular issue in U.S. society and has come to be intertwined with “tough on crime″ hardline penal policies.4 This lethal conjunction has led us to the position of having more prisoners than any country in the world by an enormous margin while being the only “western democracy″ still employing the death penalty. The following responses to Saddam Hussein’s execution in 2006 put the different views of capital punishment between the U.S. and Europe into sharp contrast. “European Commissioner for Development and Humanitarian Aid Louis Michel declared: ‘One cannot fight barbarism with means that are equally barbaric. The death penalty is not compatible with democracy’. […] British Foreign Secretary Margaret Beckett stressed that her government ‘did not support the use of the death penalty in Iraq or anywhere else’. […] American President George W. Bush hailed the news of Hussein’s death as an ‘important milestone on Iraq’s course to becoming a democracy…’.″5

Further information

Because of its use in lynching, death by hanging has a particular significance in the United States. It can be understood as a racialized form of execution in a way that no other method can.6 This historical connection between capital punishment and race is more evident today than ever with the grossly disproportionate application of the death penalty to African Americans. Not surprisingly it is the southern states that continue to carry out the majority of executions today.7

There are several arguments for the abolition of the death penalty, among them is the fact that capital punishment does not reduce or prevent crime. The death penalty is known to be the least effective form of punishment by law enforcement and criminologists. It is more expensive to kill a prisoner than to keep him in prison for life. It is applied disproportionately to people of color, the poor and the uneducated. And perhaps most damning of all, it has been proven that innocent people have been executed through wrongfully convictions. The United States is the only “western democracy″ that currently employs the death penalty, joining China, Iran, Pakistan, Iraq, and Sudan as the world leaders in executions.8 It continues to execute juveniles: the first child killed on the continent was in the Plymouth Colony in 1642 beginning a grisly tradition in American jurisprudence.

Capital punishment is a highly contentious issue in the United States, although public opinion polls show that the majority of Americans favor life without parole over the death penalty. In spite of this the US media rarely covers arguments for abolition of the death penalty. In this climate it has become virtually impossible for any politician to campaign against it. George Ryan, the former Republican Governor of Illinois is a particularly chilling example. Governor Ryan was a conservative Republican elected with a strong “law and order″ position. However, after a number of prisoners on Death Row were exonerated based on new evidence showing them to be innocent he placed a moratorium on capital punishment in Illinois.9 For this act of common sense not only was he not reelected, after he left office he was subjected to a systematic campaign of politically motivated legal harassment. Ryan’s case was a clear message to other politicians about the dangers of taking on capital punishment. Even liberal Democrats must advocate hard line policies if they expect to get elected. Supporting the death penalty has become the accepted code for a “tough on crime″ platform.10 Politicians from both parties play on the citizenry’s irrational and disproportionate fear of crime. Lurid fantasies of rape, murder and mayhem are trotted out to predictable results.11

We now know that one in one hundred U.S. citizens are in jail and one in nine African American men are in prison. More young African American men are under the control of the criminal justice system than are in college. We are increasingly criminalizing our youth and militarizing our primary and secondary schools in what has become known as the “school to prison pipeline″. The nation leads the world in the total number of prisoners by a wide margin and prison spending outpaces education in many states. We know that innocent people have been executed and that there are many potentially innocent prisoners sitting on death row today.12 It is to this context that Scaffold is addressed.

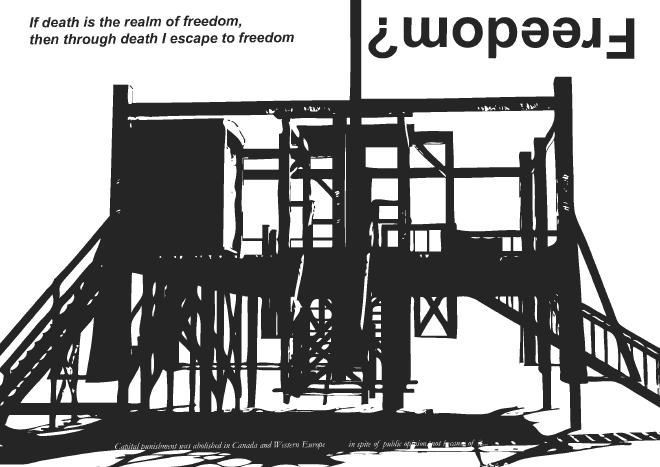

Freedom - Zine for dOCUMENTA (13) (2012) #

See “Stop the School to Prison Pipeline″, in: Rethinking Schools, Vol. 26, No. 2, Winter 2011-12. ↩︎ Although Hussein’s death sentence and execution were not carried out on US soil it can be argued that it is a part of U.S. history and is an important moment worth considering within the context of this project. ↩︎ In 1972 The U.S. Supreme Court ruled against the constitutionality of executions in Furman v. State of Georgia. In 1976 this decision was overturned in Gregg v. Georgia allowing states to re-institute the death penalty. The state of Utah made Gary Gilmore the first prisoner executed in the wake of the Gregg decision, thus beginning what is referred to as the contemporary era of capital punishment in the United States. ↩︎ Gottschalk, Marie, “The Long Shadow of the Death Penalty: Mass Incarceration, Capital Punishment and Penal Policy in the United States″ in Sarat, Austin and Jürgen Martschukat, Is the Death Penalty Dying: European and American Perspectives. New York, Cambridge University Press, 2011. ↩︎ Kathryn A. Heard, “Unframing the Death Penaly: Transatlantic Discourse on the Possibility of Abolition and the Execution of Saddam Hussein″ in Sarat, Austin and Jürgen Martschukat, Is the Death Penalty Dying: European and American Perspectives. New York, Cambridge University Press, 2011. ↩︎ The recent case of the Jena 6 serves as powerful reminder of both the continuing symbolic power of the noose, and the myth that the U.S. has “overcome″ racism. See “Justice in Jena!″ Free the Jena 6 Website, 2006. ↩︎ “Racial Disparities in Federal Death Penalty Prosecutions 1988-1994″, Death Penalty Information Center, March 1994. ↩︎ From “Death Penalty Information Center.″ The Death Penalty: An International Perspective, 2007. ↩︎ The Innocence Project was instrumental in this situation. See “The Innocence Project.″ The Innocence Project Homepage, 1992, The Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law at Yeshiva University, 28 February 2008. ↩︎ Barack Obama, the Democratic Party nominee for President is in favor of capital punishment. ↩︎ Racial fears are often invoked in this context - one of the most infamous examples was during the 1988 presidential campaign between George Bush Sr. and Mike Dukakis. The so-called “Willie Horton″ advertising campaign in which mug shots of a very dark skinned convicted rapist were broadcast across the nation to devastating effect. William Horton was an African American imprisoned in Massachusetts while Dukakis was Governor. As was the case with all qualifying prisoners he was released on weekend furloughs as part of the State’s prison rehabilitation program. Horton never returned to prison from a furlough and later was convicted of rape and robbery in Maryland. Bush’s campaign produced an ad featuring Horton’s menacing mug shot designed to stoke racial fears. It was “every suburban mother’s nightmare″ as Bush’s media consultant called it and was instrumental in his election victory. ↩︎ Aizenman, N.C.. “New High In U.S. Prison Numbers″, Washingtonpost.com, 29 February 2008; Pew Center on the States report, One in 100: Behind Bars in America, 2008. ↩︎

Downloadable PDF of self published ‘zine that was available to visitors to dOCUMENTA (13), 2012 in Kassel, Germany

Images #

Wood, metal

33.73’ × 47.47’ × 51.77’

Photo credit: Rosa Maria Ruehling; Commissioned and produced by dOCUMENTA (13)

Wood, metal

33.73’ × 47.47’ × 51.77’

Photo credit: Rosa Maria Ruehling; Commissioned and produced by dOCUMENTA (13)

Wood, metal

33.73’ × 47.47’ × 51.77’

Photo credit: Rosa Maria Ruehling; Commissioned and produced by dOCUMENTA (13)

Wood, metal

33.73’ × 47.47’ × 51.77’

Photo credit: Rosa Maria Ruehling; Commissioned and produced by dOCUMENTA (13)

Wood, metal

33.73’ × 47.47’ × 51.77’

Photo credit: Rosa Maria Ruehling; Commissioned and produced by dOCUMENTA (13)

Wood, metal

33.73’ × 47.47’ × 51.77’

Photo credit: Rosa Maria Ruehling; Commissioned and produced by dOCUMENTA (13)

Wood, metal

33.73’ × 47.47’ × 51.77’

Photo credit: Rosa Maria Ruehling; Commissioned and produced by dOCUMENTA (13)

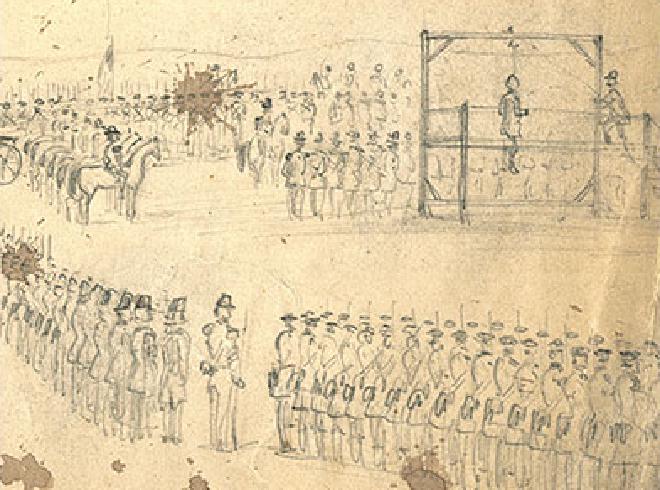

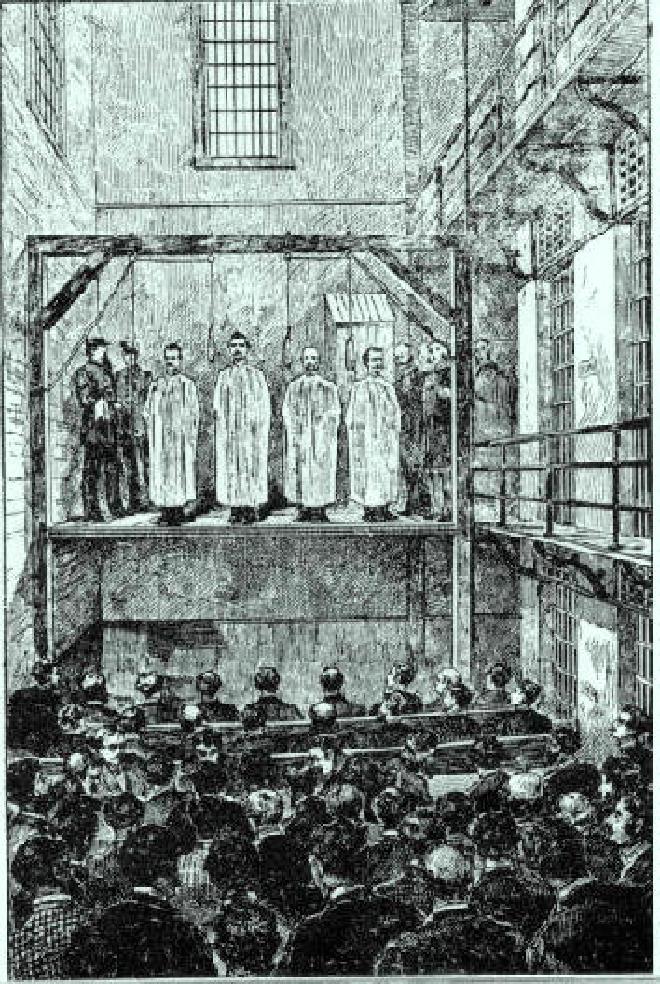

This drawing depicts the hanging of John Brown, the most well known militant white abolitionist. Brown gave his life to the struggle to end slavery, becoming an icon of the movement. He was charged with treason, conspiracy, and the murder of five men during the raid he organized on the Harpers Ferry armory on July 3, 1859. Ten of Brown’s twenty-one men were killed (including his sons Watson and Oliver). Five escaped (including his son Owen) and seven were captured along with Brown. John Brown was hanged in public on December 2, 1859, escorted by 2,000 soldiers. Those hanged besides Brown were John Anthony Copeland, Jr. and Shields Green.

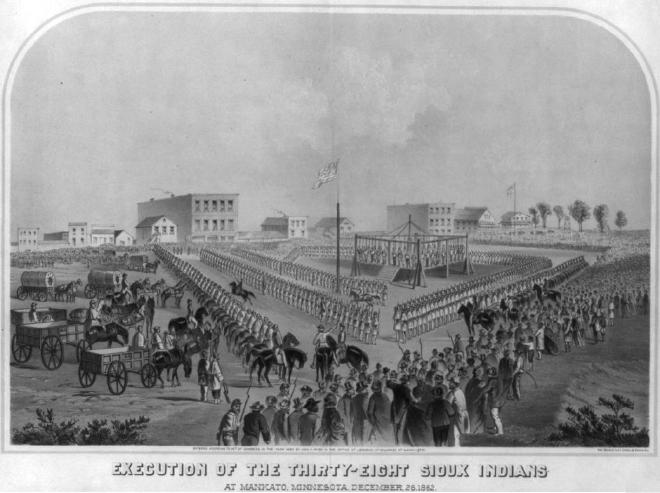

This is the notorious gallows that hanged 38 Santee Sioux Indians, the largest mass execution in U.S. history. On December 26, 1862, the men were hung, having been convicted of rape and murder during the conflict known as the Dakota Wars. White settlements had consumed virtually all of the Santee and Dakota lands in what would become Minnesota, as the Indians began to starve they also began to fight back. Authorities in the state asked President Lincoln to order the immediate execution of all 303 Indians found guilty. Lincoln reduced the list to 39 (One was reprieved at the last minute), and agreed to provide Minnesota with 2 million dollars in federal funds to remove the remaining Indians from the state’s land. The remaining Santee/Dakota population was then imprisoned in a squalid encampment near Fort Snelling before being removed to reservations. This was the first use of ethnically targeted mass internment by the federal government, a technique that was subsequently employed throughout the 19th century “Indian Wars” and most recently during WWII with Japanese Americans.

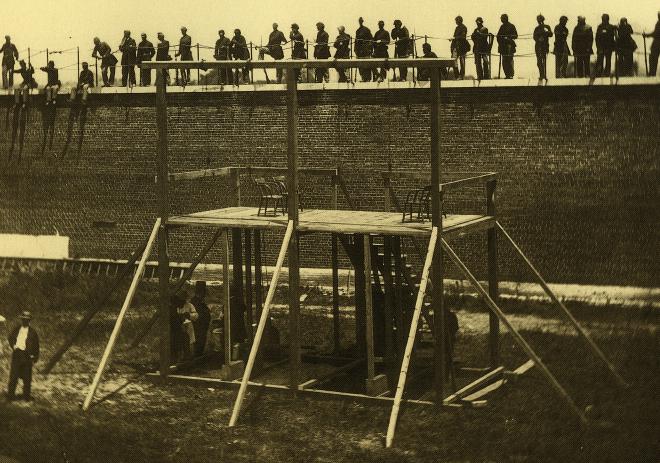

On July 7, 1865, four of the nine conspirators charged with attempting to overthrow the Union government were hanged after being tried by a military tribunal. John Wilkes Booth, who assassinated President Lincoln, was shot dead during his attempted arrest. Lewis Powell (a.k.a. Lewis Paine) and David Herold were hanged for their attempt to murder William H. Seward, then Secretary of State. George Atzerodt and Mary Suratt, the first woman to be executed by the U.S. government, were hanged for their involvement in aiding and abetting the crimes. Approximately 1,000 people attended the hanging, a number that was limited by the distribution of tickets. The hanging took place in the Old Arsenal Penitentiary, Washington, D.C.

This is the gallows from which four anarchists—August Spies, Albert Parsons, Adolph Fischer, and George Engel–were hanged in Chicago in connection with the Haymarket massacre. On May 4, 1886 a peaceful public meeting in support of striking workers was violently interrupted by an explosion in Haymarket square, killing policeman Mathias J. Degan. The police response and ensuing gunfire and panic resulted in the deaths of seven more police officers, 4 workers, and an unknown number of civilians. Despite rumors that Pinkerton agents had provoked the incident, eight anarchists were tried for murder and conspiracy. Spies, Parsons, Fischer, and Engel were hanged on November 11, 1887, Louis Lingg committed suicide in prison the night before his scheduled execution, Oscar Neebe was sentenced to 15 years in prison, Samuel Fielden and Michael Schwab were sentenced to life in prison. Reassembled pieces of this gallows were used in the Cook County Jail in Chicago from 1887 until 1927 when the electric chair replaced hanging as the primary method of execution. The gallows remained in the Cook County Jail storage until 1977, served as a prop at a Wild West museum for 29 years after that, and was sold at auction in 2006 to Ripley’s Believe it or Not Museum.

The site of the last legally conducted public hanging in the U.S.. Rainey Bethea, a 26 year old black man, was hanged on August 14, 1936, in Owensboro, Kentucky, after being convicted for raping Lischia Edwards, a 70 year old white woman. Edwards was murdered in addition to being raped, but Bethea was charged solely with rape because, under the Kentucky law, charges of murder and robbery resulting in a death penalty were carried out by electrocution in the state penitentiary at Eddyville. However, rape could be punished by public hanging in the county seat where the crime occurred. To avoid a potential legal dilemma as to whether Bethea would be hanged or electrocuted, the prosecutor elected to charge Bethea only with the crime of rape. He was never charged with the remaining crimes of theft, robbery, burglary, or murder. After only an hour and forty minutes, the grand jury returned an indictment, charging Bethea with rape. At the time of the conviction, the presiding sheriff was a woman named Florence Thompson. Public outcry in protest against a female executioner caused Thompson to accept former police officer Arthur L. Hash’s offer to perform the execution.

This wooden gallows was built on the grounds of the Delaware Correctional Center in 1986 and was the site of the last execution by hanging in the United States. In 1996, Billy Bailey became the third and last person to be hanged in America since the resumption of executions in 1977. At the time of Bailey’s execution, prisoners who received the death penalty in Delaware were given a choice between lethal injection and hanging. In 1996, this law was changed so that only those convicted prior to that year would be allowed to choose hanging. Since Bailey was the last prisoner in this category, the gallows were dismantled.

The execution of former Iraqi President Saddam Hussein took place on December 30, 2006. On June 30, 2004, Hussein was charged with war crimes, crimes against humanity, genocide, and the 1982 murder of 148 Iraqi Shi’ites in Dujail. On November 5, 2006, the Iraqi Special Tribunal found Hussein guilty of crimes against humanity and sentenced him to death by hanging. The hanging took place at Camp Justice, a joint Iraqi-American military base in Kadhimiya, Iraq. His co-defendants Barzan Ibrahim al-Tikriti and Awad Hamed al-Bandar were later executed on January 15, 2007.