- / Work/

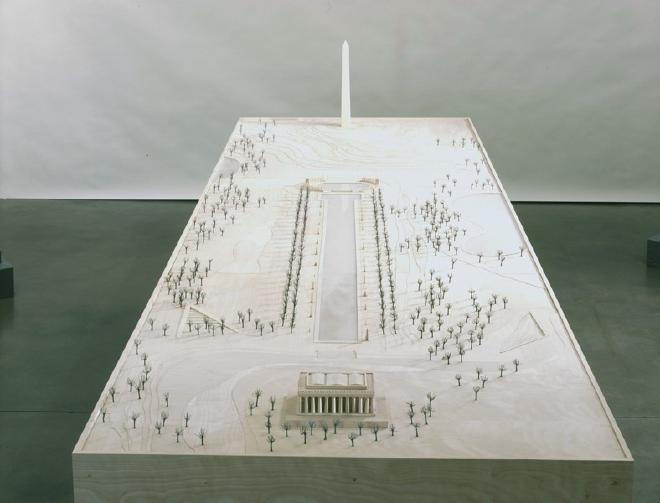

Proposal for White and Indian Dead Monument Transpositions, Washington, D.C.

On this page

Images #

MDF, fiberglass, foam, enamel, acrylic, basswood, balsa wood, birch veneer, and copper

30 monuments: dimensions vary, architectural model 48″ × 150″ × 16″

MDF, fiberglass, foam, enamel, acrylic, basswood, balsa wood, birch veneer, and copper

30 monuments: dimensions vary, architectural model 48″ × 150″ × 16″

MDF, fiberglass, foam, enamel, acrylic, basswood, balsa wood, birch veneer, and copper

30 monuments: dimensions vary, architectural model 48″ × 150″ × 16″

MDF, fiberglass, foam, enamel, acrylic, basswood, balsa wood, birch veneer, and copper

30 monuments: dimensions vary, architectural model 48″ × 150″ × 16″

MDF, fiberglass, foam, enamel, acrylic, basswood, balsa wood, birch veneer, and copper

30 monuments: dimensions vary, architectural model 48″ × 150″ × 16″

MDF, fiberglass, foam, enamel, acrylic, basswood, balsa wood, birch veneer, and copper

30 monuments: dimensions vary, architectural model 48″ × 150″ × 16″

MDF, fiberglass, foam, enamel, acrylic, basswood, balsa wood, birch veneer, and copper

30 monuments: dimensions vary, architectural model 48″ × 150″ × 16″

MDF, fiberglass, foam, enamel, acrylic, basswood, balsa wood, birch veneer, and copper

30 monuments: dimensions vary, architectural model 48″ × 150″ × 16″

MDF, fiberglass, foam, enamel, acrylic, basswood, balsa wood, birch veneer, and copper

30 monuments: dimensions vary, architectural model 48″ × 150″ × 16″

MDF, fiberglass, foam, enamel, acrylic, basswood, balsa wood, birch veneer, and copper

30 monuments: dimensions vary, architectural model 48″ × 150″ × 16″

MDF, fiberglass, foam, enamel, acrylic, basswood, balsa wood, birch veneer, and copper

30 monuments: dimensions vary, architectural model 48″ × 150″ × 16″

MDF, fiberglass, foam, enamel, acrylic, basswood, balsa wood, birch veneer, and copper

30 monuments: dimensions vary, architectural model 48″ × 150″ × 16″

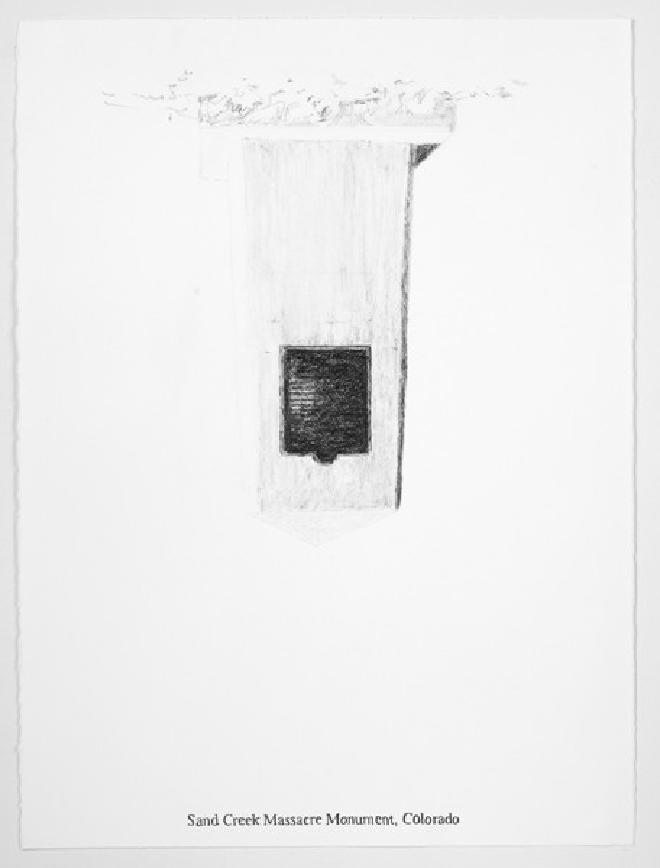

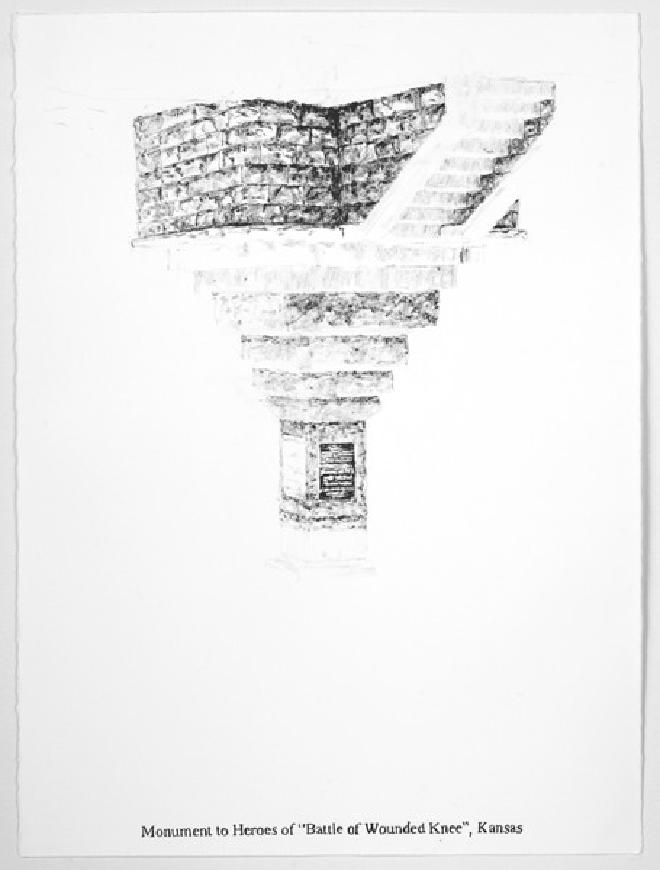

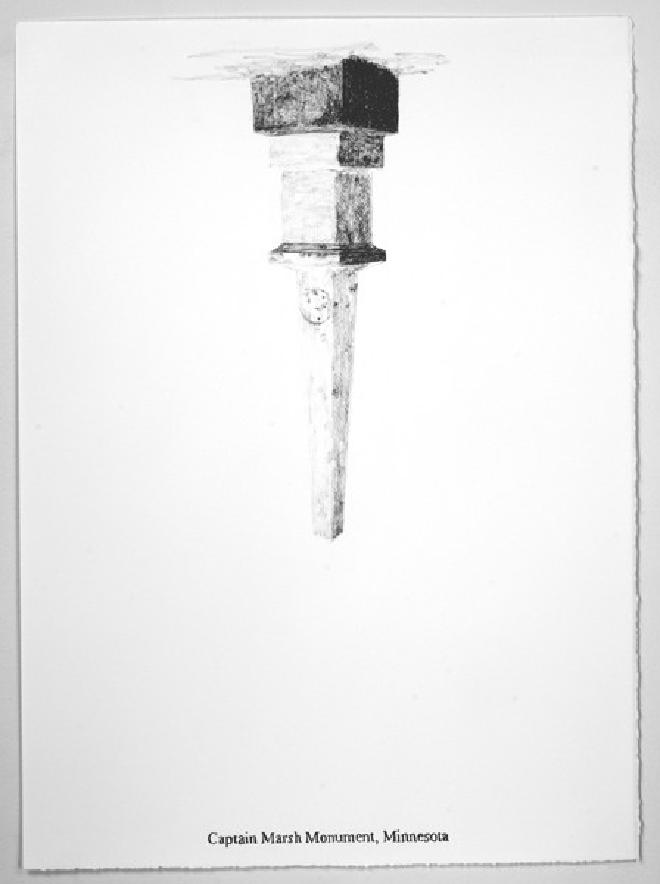

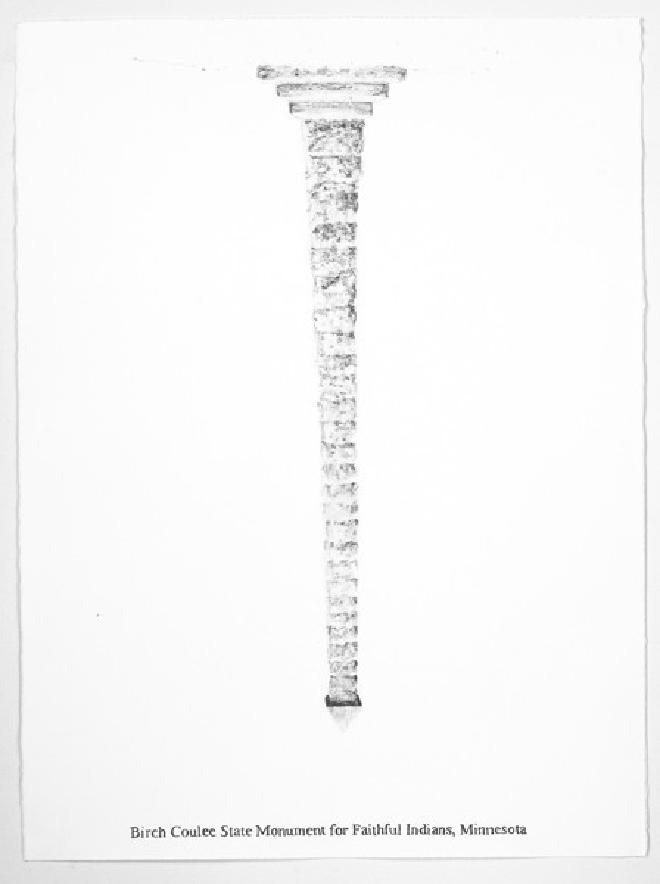

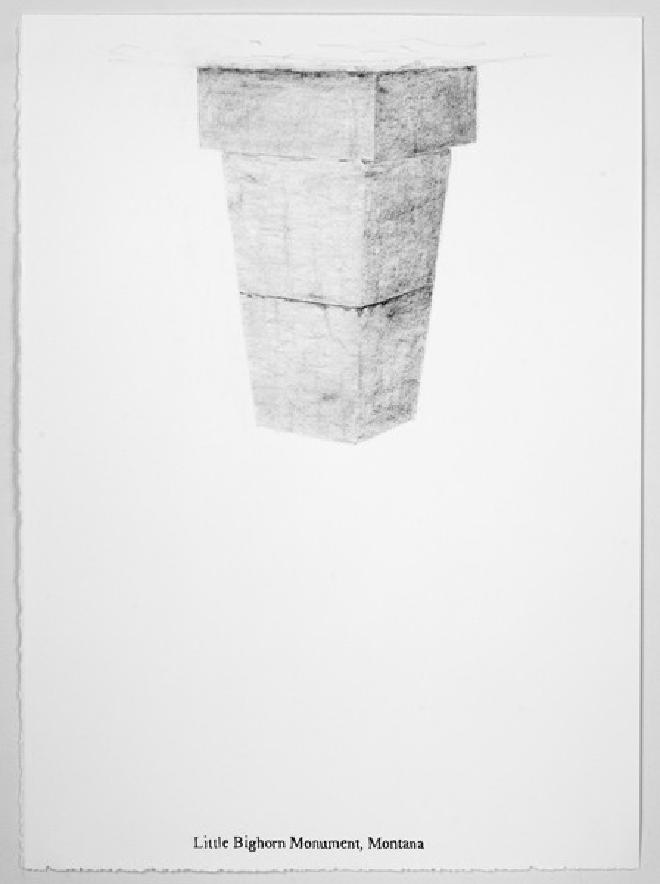

Graphite on paper

30″ × 22″

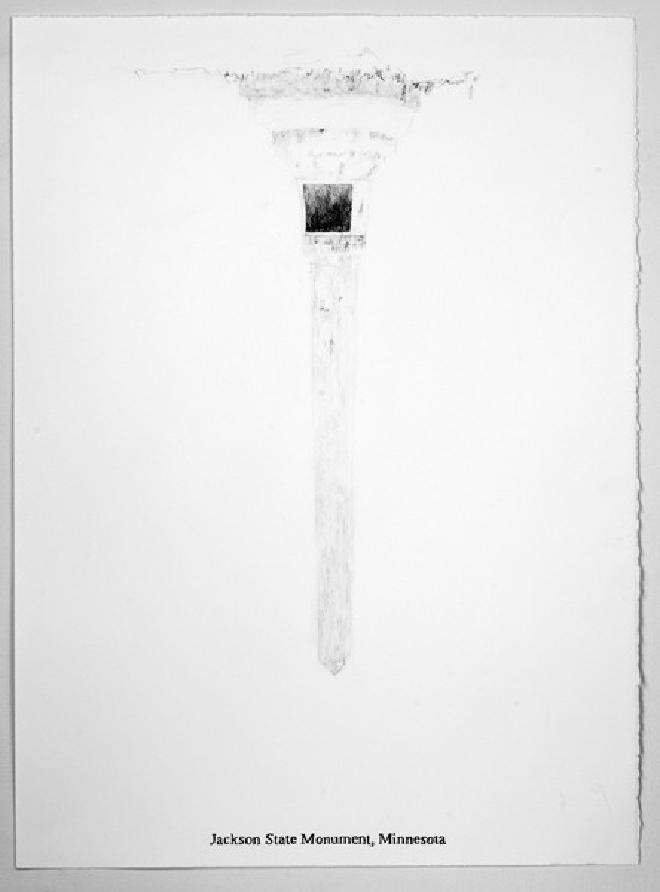

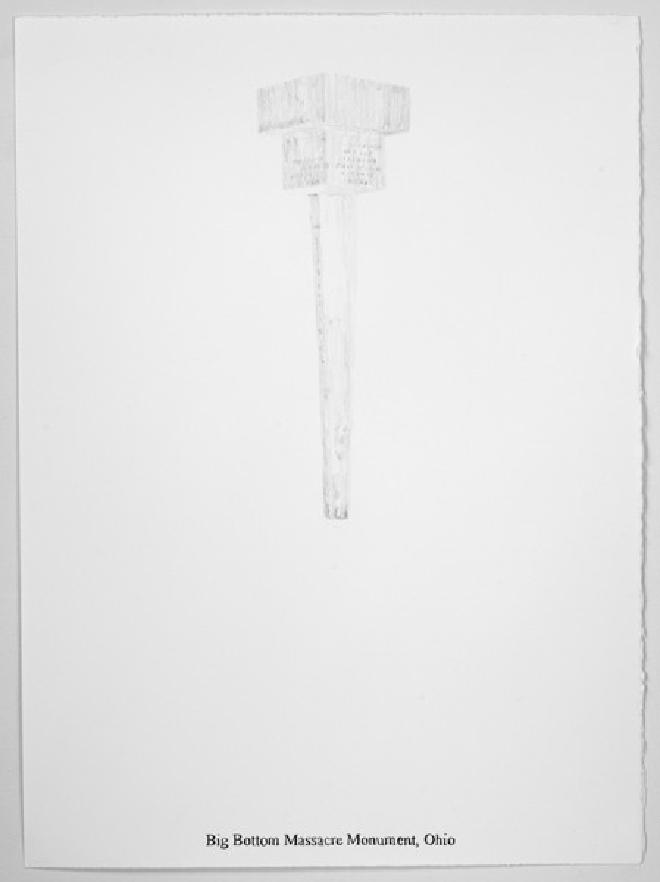

Graphite on paper

30″ × 22″

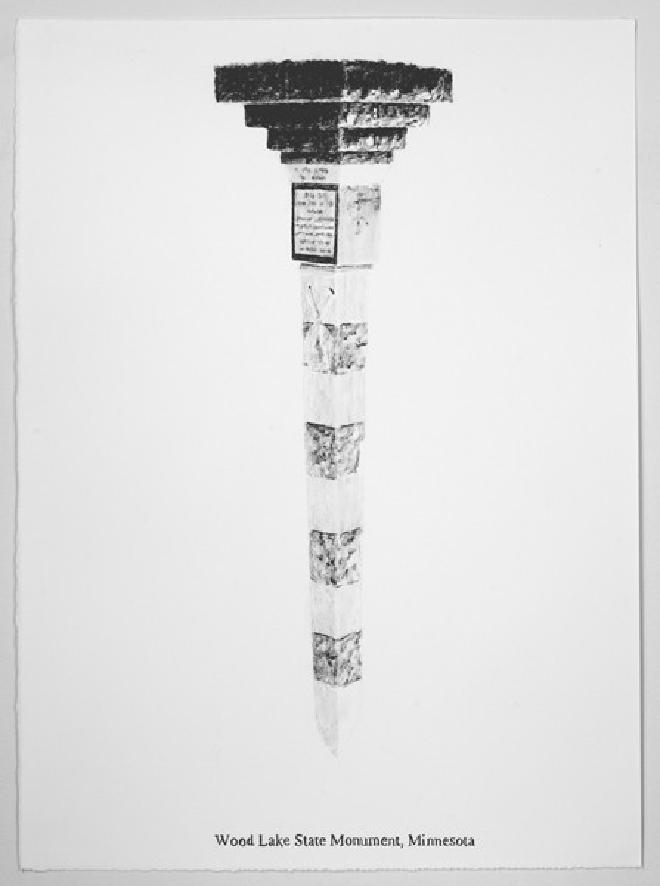

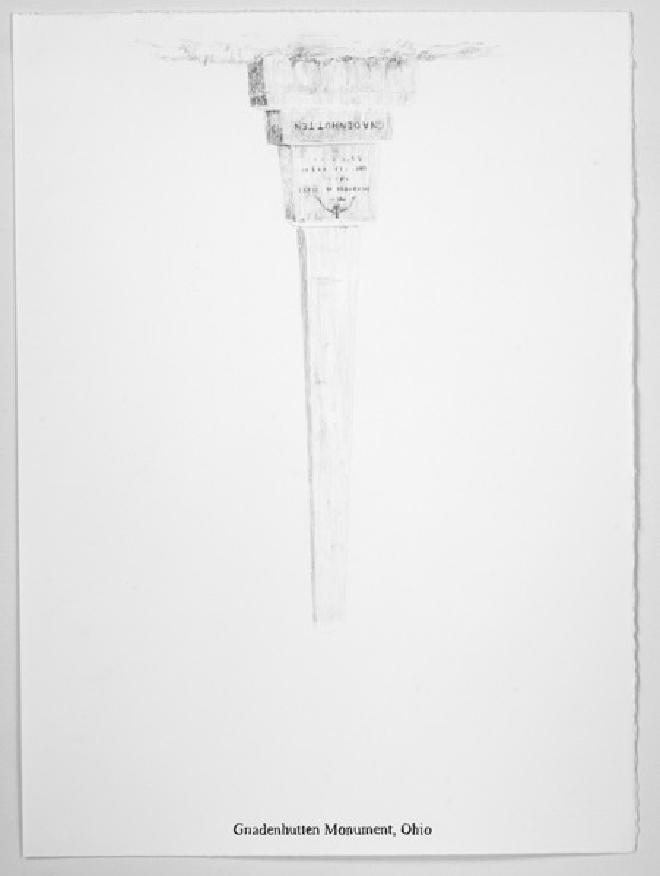

Graphite on paper

30″ × 22″

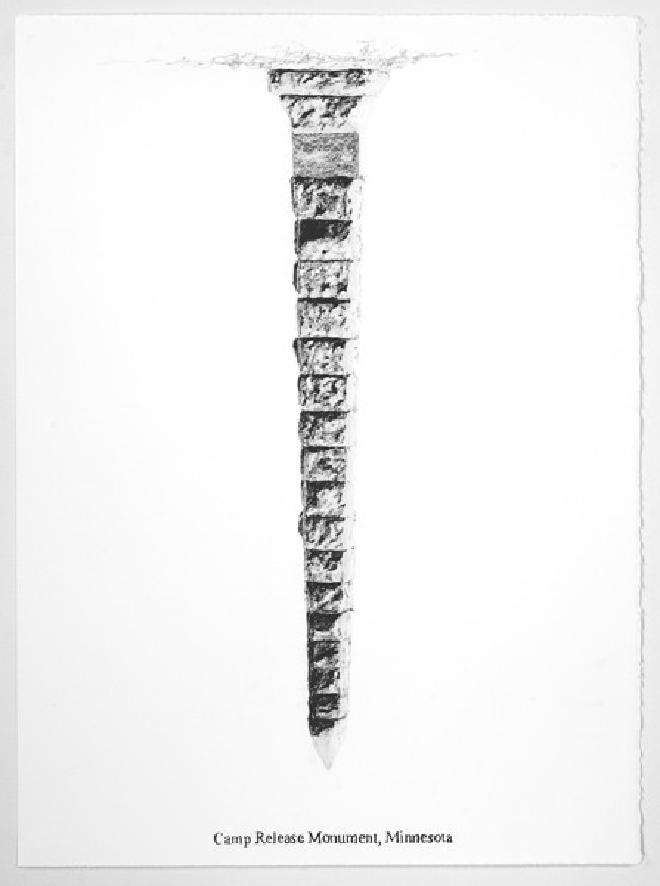

Graphite on paper

30″ × 22″

Graphite on paper

30″ × 22″

Graphite on paper

30″ × 22″

Graphite on paper

30″ × 22″

Graphite on paper

30″ × 22″

Graphite on paper

30″ × 22″

Graphite on paper

30″ × 22″

Graphite on paper

30″ × 22″

Graphite on paper

30″ × 22″

Graphite on paper

30″ × 22″

Graphite on paper

30″ × 22″

Graphite on paper

30″ × 22″

Graphite on paper

30″ × 22″

Graphite on paper

30″ × 22″

Graphite on paper

30″ × 22″

Graphite on paper

30″ × 22″

Graphite on paper

30″ × 22″

Graphite on paper

30″ × 22″

Graphite on paper

30″ × 22″

Graphite on paper

30″ × 22″

Graphite on paper

30″ × 22″

Graphite on paper

30″ × 22″

Graphite on paper

30″ × 22″

Graphite on paper

30″ × 22″

Graphite on paper

30″ × 22″

Graphite on paper

30″ × 22″

Graphite on paper

30″ × 22″

Text #

Scattered across the continental United States are numerous monuments, markers and memorials that commemorate massacres during the colonization of North America. The massacre monuments are representative of the beginning of US history, starting with Columbus’ “discovery″ of the New World through the territorial solidifying of the Union after the Civil War. These massacre monuments reflect the violent and unequal relationship between whites and Native Americans during the creation of the republic. While they memorialize victims from the 17th century to the end of the “Indian Wars″ in 1890, the monuments themselves were erected primarily in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Against these geographically dispersed massacre sites, the father of all monuments is fittingly located in the nation’s capital. A 555-foot stone obelisk, the Washington Monument towers over the numerous monuments and memorials located on the National Mall. Under the shadow of this massive stone pillar, multitudes visit the Mall each year with the goal of gaining a deeper understanding of the country and its history. It is within this official history of the nation, its wars and its military and political policies, that my proposal situates itself.

The Proposal for White and Indian Dead Monument Transpositions consists of relocating a selection of existing massacre monuments and memorials from around the country to the National Mall in Washington, D.C. The monuments and memorials to be moved conform to specific criteria. They must be permanent markers commemorating massacres involving groups of whites and Indians. Figurative markers or statues are generally ruled out, as they tend to refer to individuals. Plaques, cairns, gravestones and non-sculptural markers are also disqualified in the interest of maintaining the formal category of the vertical shaft. The chosen monuments should be understood, through physical similarity, in relation to the massive obelisk of the Washington Monument. Unsurprisingly, the great majority of the monuments honor whites. The layout of the monuments and memorials on the National Mall will reflect this discrepancy by a separation into two groups. The monuments to the white dead will be located on either side of the reflecting pool that runs between the Lincoln Memorial and the Washington Monument. The monuments and memorials to the Indian dead will be installed on the lawn area directly in front of the Washington Monument. The proposal calls for this separation in order to foreground certain aspects of the way history is produced, to raise the question of who controls history and whose interests it serves. It also points to the current territorial context of the reservations: the sovereign Indian Nations within the United States. Another aspect of the proposal is to suggest that the application of violence, repression and inequality is harmful not just to its victims but to its supposed beneficiaries as well. The deaths that are commemorated by the transposed memorials are not those of the rulers, but those who died anonymously for their gain, both white and Indian.

The relatively few monuments devoted to Native American lives are primarily dedicated to “friendly Indians,″[^0] the innocent victims of righteous war. These monuments were erected by whites to serve their own interests and do not represent Indian perspectives, experiences or interests. A particularly striking example is the monument at Gnadenhutten, Ohio. It commemorates ninety-six Christian Mohicans who were massacred in 1782. The Mohicans were co-existing peacefully and assimilating to white civilization. They were slaughtered by American troops in retaliation for an earlier Indian raid on white settlers in which they played no part. Foreshadowing the many massacres to come, this is one of the first mass executions of innocent non-combatants by the forces of the freshly constituted U.S. Government.

The two monuments in Birch Coulee, Minnesota provide another noteworthy but more complex case. These monuments are among many commemorating the Dakota Uprising of 1862 which marked the beginning of the “Indian Wars″. The Dakota Sioux, under intense pressure had signed treaties relinquishing nearly all of their land in exchange for yearly annuity payments. As white settlers spread across Minnesota, the Sioux were forced onto tiny reservations with few resources. Without means to subsist, they became dependent on the annuities to survive. White storeowners acted as the agents for distributing the annuities, which consisted mostly of food and supplies. After a severe drought and crop failures that year, the storeowners refused to give the Dakota their payments, one of them callously stating “If they are hungry, let them eat grass.″1 Although there were many factors leading to the uprising, being denied their disbursements while on the verge of starvation proved to be the breaking point. Some historians have come to acknowledge that the Indians were justified in their actions against the settlers under these conditions.2 But the monuments erected to remember the lives lost in this struggle tell another story. At Birch Coulee one monument commemorates the American soldiers killed while the other one commemorates the friendly Indians who helped save white settlers during the Uprising. Tellingly, there is no monument to the Indians who lost their lives fighting for their survival against an enemy that was trying to starve them out of existence. Despite the appearance of equality, it can be understood that both markers at Birch Coulee reflect and serve exclusively white experiences and interests.3 The memorials dedicated to Dakota Uprising events also unintentionally point to the way in which white settlers were used for the purpose of territorial expansion. Under the guise of manifest destiny, pioneers were often given parcels of land within Indian Territory. As conflicts inevitably erupted they were often on the receiving end of the ubiquitous violence that resulted from the republic’s methods of land acquisition. Many of the settlers killed during this period were simply canon fodder for the expansion of the union.

A comparison of another set of monuments demonstrates the uninterrupted and continuously asymmetrical relationship between whites and Indians. The monuments in question are both from battles late in the Indian Wars period: Little Big Horn and Wounded Knee (which marked the end of the Indian Wars). An examination of the type and condition of the markers along with their surroundings reveals both the historical and contemporary disparity between Indians and whites. Little Big Horn in Montana was the site on which General Custer met his end in 1876. Thinking he would ride unmolested into a Sioux encampment at the Little Big Horn River and massacre the inhabitants, he boasted, “I can whip all the Indians on the Continent with the Seventh Cavalry.″4 Instead, he met with the largest Native American force yet assembled, consisting of Northern Cheyenne, Hunkpapa and Oglalla Sioux united in self-defense. Led by Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull, the Indians crushed Custer and his troops, killing nearly all of them. Having graduated last in his class at West Point, Custer was an inept, vain and unprepared commander who made virtually every mistake possible in his final engagement. A more appropriate response to his actions at Little Big Horn might have been a dishonorable discharge; his hubris and incompetence resulted in the deaths of 260 men under his command. Instead a monument was erected in which he was portrayed as a heroic warrior, fighting bravely against overwhelming odds. The battlefield site at Little Big Horn is a designated National Monument and was until recently known as the Custer Battlefield. Billed as “Living History,″ Little Big Horn sports all the trappings of a well-funded National Park, complete with walking trails, interpretive markers around the battlefield, well-maintained grounds, a gift shop, and a memorial to the victims of the battle.5 6

Standing in stark contrast to Little Big Horn’s manicured civility is the marker to Big Foot’s band, massacred at Wounded Knee in 1890. The same Seventh Calvary that had been routed at Little Big Horn enacted their revenge by slaughtering the starving, virtually unarmed Indians. By all definitions the brutal massacre of some 200 Lakota should be classified as a war crime, yet twenty of the soldiers responsible received the Congressional Medal of Honor for extraordinary valor in battle. Through the efforts of the Wounded Knee Survivors Association the victims of this massacre did, however, receive a monument in 1903.7 The Wounded Knee monument is situated on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, the poorest county in America, where more than half of the residents live below the poverty line. The memorial sits amidst a rundown graveyard on top of the mass grave.[^8| The disparity between the Little Big Horn and Wounded Knee monuments provides a graphic example of how little the balance of power has changed in the one hundred and fifteen years since the conclusion of the “Indian Wars″.8

Collectively the various monuments and memorials in my proposal both define and are defined by this history. By re-contextualizing the monuments the proposal seeks to foreground the role of violence in the formation of the United States and to raise questions about the function of monuments and memorials in that equation. While violence is undoubtedly central to the many war memorials on the National Mall, their task is to justify and validate the loss of life as a necessary sacrifice in the preservation of the “American way of life″ and by extension the state. The monuments do not raise questions about the conflicts or the use of violence, nor do they reveal the powerful interests that drove these conflicts. Rather, they provide a guise of neutrality and necessity through their authoritative presence.

Likewise, the massacre monuments in my proposal, regardless of whom or what they commemorate do not provide a balanced historical record. They also do not raise questions about the impossibility of doing so, nor are they meant to. They are, in fact, meant to do the opposite. The monuments’ function is to provide a historical narrative that validates and justifies violence and loss of life through the commemoration of the victorious and with the authority of their physical presence. The gesture of transposing the massacre monuments into the context of the National Mall seeks to underscore this traditional function, making it so obvious as to be unavoidable. Within this new situation the meaning of the monuments, the authority of their historical narratives and their intended, “official″ functions might be opened to analysis and questioning.9

-

Kenneth Carley, The Dakota War of 1862 (Minneapolis, MA: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1976), pg. 6. ↩︎

-

See The Dakota War of 1862 herein for an in-depth study of the Uprising and its aftermath. ↩︎

-

Only since the 1970s the empowerment struggles of Native American groups like A.I.M. and others have there been any monuments erected by Native Americans and reflective of their experiences. An example would be the recently installed plaque at Plymouth Rock acknowledging that many indigenous people do not celebrate the arrival of the Pilgrims because: “To them, Thanksgiving day is a reminder of the genocide of millions of their people, the theft of their land and the relentless assault on their culture.″ ↩︎

-

T. Harry Williams, The History of American Wars, (New York, Alfred A. Knopf Inc, 1981), pg. 315. ↩︎

-

According to National Park Service records its budget for 2004 was $1,029,000. ↩︎

-

See Christian Parenti, Why Not Wounded Knee, (www.alternet.org, 2002). ↩︎

-

The first Wounded Knee monument was erected in 1893 and is located in Fort Riley, Kansas. It is dedicated to the 25 soldiers who died. ↩︎

-

In 1995 a bill proposing a new memorial was put to the United States Congress but the bill has not yet passed, and there is still much conflict about the memorial. The Wounded Knee Survivors Association is responsible for the current marker, erected in 1903. Its members are “descendents and relatives of the Sioux Indians that were involved or killed in the Wounded Knee Massacre on December 29, 1890.″ The Association originated shortly after the 1890 massacre, when survivors began to ask for compensation. Dewey Beard and Joseph Horn Cloud were two of the organization’s founding members. Currently, the Association is an independent organization whose goals include preserving and protecting the massacre site from exploitation and administering any memorial erected at the Wounded Knee site. (The Wounded Knee Survivors Association Papers, I.D. Weeks Library Archives and Special Collections, University of South Dakota). ↩︎

-

An interesting analysis and critique of the function of the Washington Monument can be found in the song Piss On Your Grave, The Coup, Steal This Album (Dogday Records, 1998). ↩︎