- / Work/

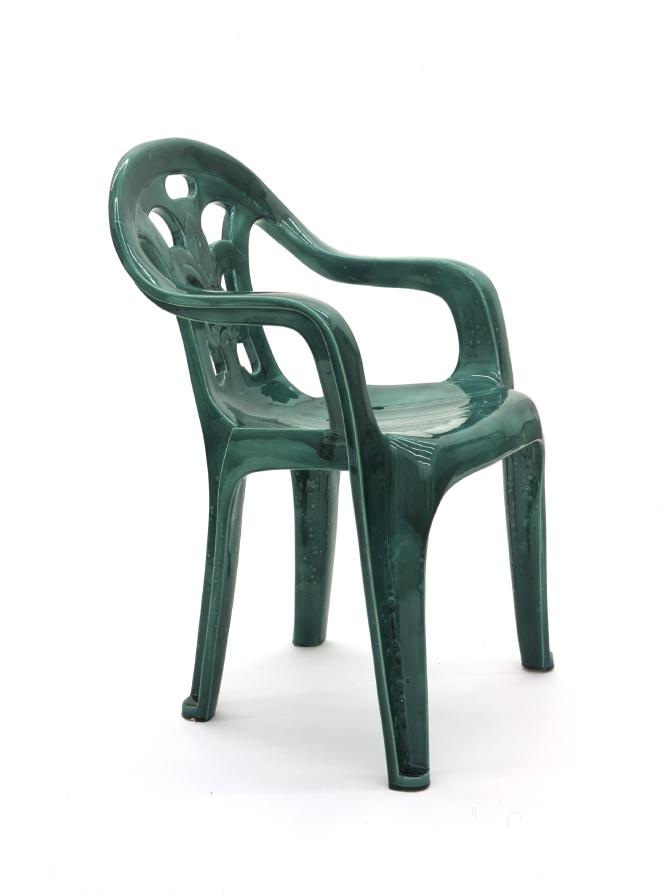

Porcelain Chairs

On this page

Images #

Glazed porcelain

31 1/2″ × 21″ × 19 1/2″

Photo credit: Joshua White

Glazed Porcelain

31 1/2″ × 21″ × 19 1/2″

Photo credit: Joshua White

Glazed Porcelain

31 1/2″ × 21″ × 19 1/2″

Photo credit: Joshua White

Glazed porcelain

31 1/2″ × 21″ × 19 1/2″

Photo credit: Joshua White

Glazed porcelain

31 1/2″ × 21″ × 19 1/2″

Photo credit: Joshua White

Glazed porcelain

18″ × 18″ × 30″

Photo credit: Joshua White

Glazed porcelain

31 1/2″ × 21″ × 19 1/2″

Photo credit: Joshua White

Glazed porcelain

18″ × 18″ × 30″

Photo credit: Joshua White

Glazed porcelain

31 1/2″ × 21″ × 19 1/2″

Photo credit: Joshua White

Installation view, Blum and Poe, Los Angeles

Glazed porcelain

Dimensions vary

Photo credit: Joshua White

Installation view, Blum and Poe, Los Angeles

Glazed porcelain

Dimensions vary

Photo credit: Joshua White

Text #

This work consists of nine unique, porcelain reproductions of different styles of mono-block resin chairs. The chairs were made by crafts people at the Jiao Zhi studio in Xiamen, China, completely by hand, no molds were taken from the originals. The place and method by which they were made is important to the meaning of the work in several ways, most obviously as it contrasts with the manufacturing process of the mass-produced resin chair on which it is based. Mono-block resin chairs are made using the injection molding process. There is no patent or copyright on the design or manufacturing technique, allowing for limitless production of virtually identical chairs. It is probably the cheapest and most universal piece of furniture, found in nearly every country in the world. Many American and European modernist designers did early research into the production of single material or mono-block furniture. Ironically, the resin chair might be the fulfillment of modernist design’s utopian vision of a modular, single material chair, industrially manufactured, cheap and widely available. It is also indicative of globalization and the spread of western (Euro-American), post-nationalist capitalism. Manufacturing of the resin chairs can be easily accomplished in the country with the cheapest labor and/or most advantageous business climate and then shipped for sale anywhere. This system, geared toward maximum profit, usually through maximum exploitation might also be seen as another type of fulfillment of western modernism.

In producing a ceramic copy of the resin chair several “transformations″ take place, allowing the viewer to make comparisons between the functional original and the “copy″ (artwork). These comparisons might extend to the economic, political and aesthetic systems in which both the mono-block resin chair and the artwork on which it is based are embedded. Utterly functional in terms of its cost-benefit ratio, western standards of taste obviously assign very little aesthetic value to the resin chair. By hand crafting it in porcelain and rendering it as a unique art work the original functionality and following low aesthetic value of the resin chair are brought into comparison with the value added status of the artwork. I titled each of the chairs with its color and the names of all the workers involved in their construction to ensure that this information will never disappear as they circulate in the art world. Foregrounding the fact that the chairs were made by Chinese fabricators introduces more comparisons for the viewer. Globalization and the liberalization of China’s economic system have enabled the spread of mass-produced goods throughout the “West″. The label “made in China″ has become synonymous with cheap and low quality. Apparently standing in contradiction to this stereotype, the hand made porcelain chairs status as objects of aesthetic value rest on the fact that they are Chinese goods, conceptually and physically. Viewers with even a modest grasp of history know that China has been producing masterpieces of ceramic art for centuries, far longer than any comparable tradition in the “west″. This contrast between China’s “cheap goods″ and its unmatched ceramic art might open another line of questioning. There is also the issue of authorship, of how my position as a recognized North American artist creates value for any work attributed to me, and especially in this case of “outsourced″ fabrication. Because I contracted with Chinese producers have I engaged in the same type of exploitation that global corporations do? Through these questions and comparisons the work’s relationship to modernism and design, to globalization and trade, to cultural history and to systems of aesthetic value and cultural capital will hopefully come into focus.