- / Work/

Invisible Surrealists

On this page

Images #

Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photo: Steven Probert.

Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photo: Steven Probert.

Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photo: Steven Probert.

Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photo: Steven Probert.

Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photo: Steven Probert.

Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photo: Steven Probert.

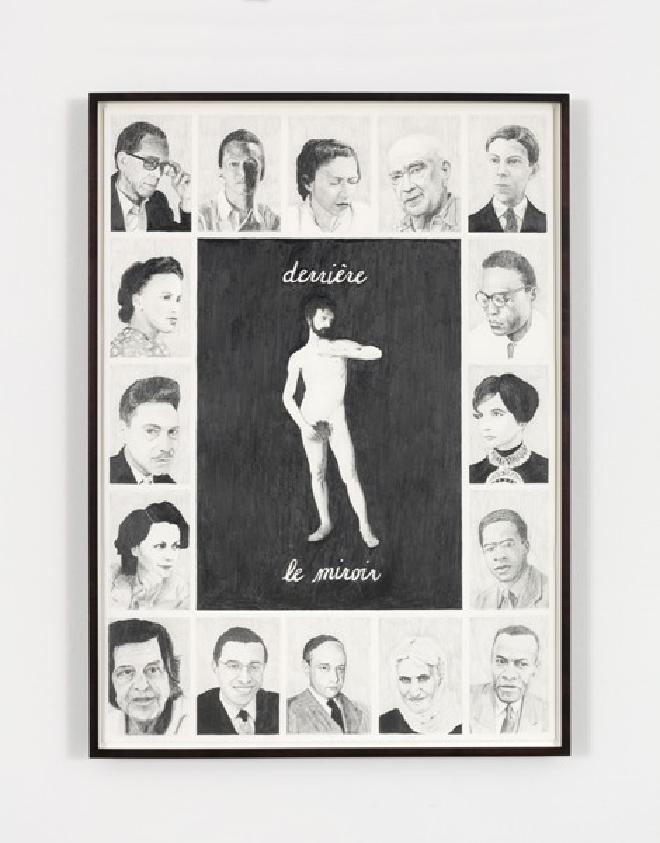

Graphite on paper

34.625″ × 24.75″

Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photo: Steven Probert.

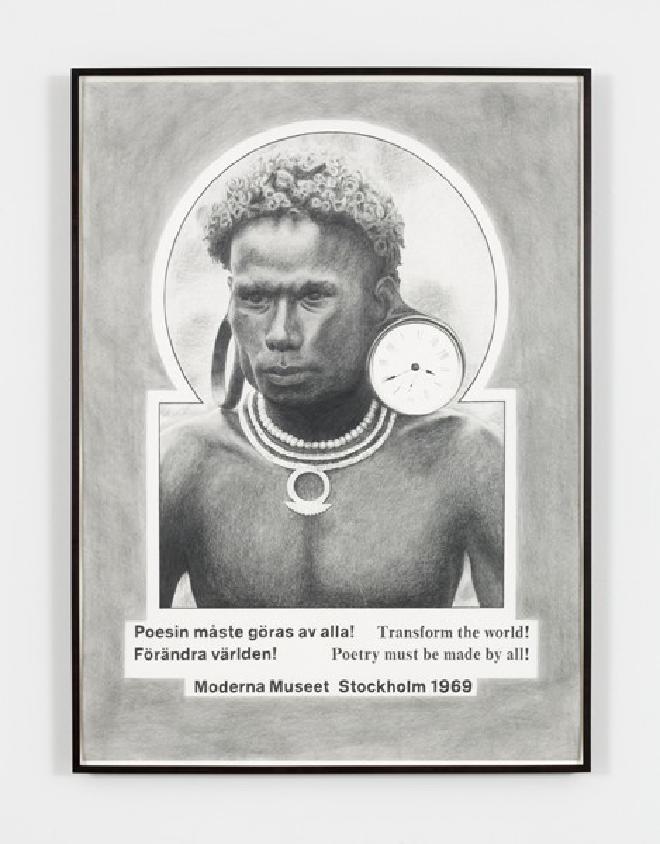

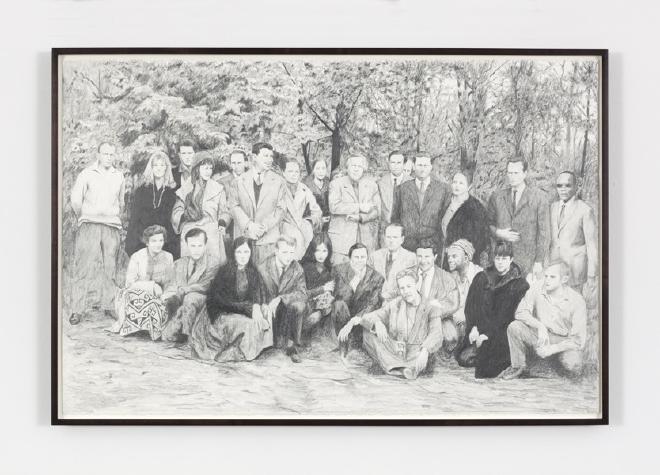

Graphite on paper

54″ × 39.5″

Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photo: Steven Probert.

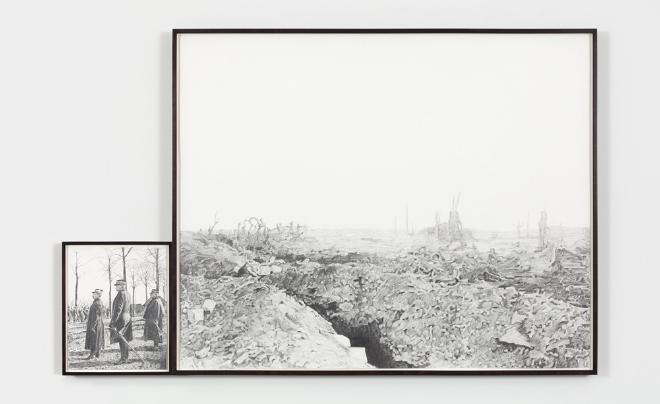

Graphite and enamel on paper

22″ × 30″

Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photo: Steven Probert.

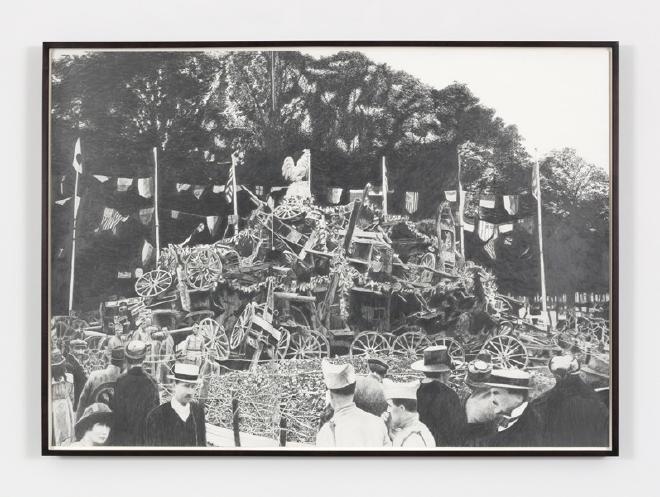

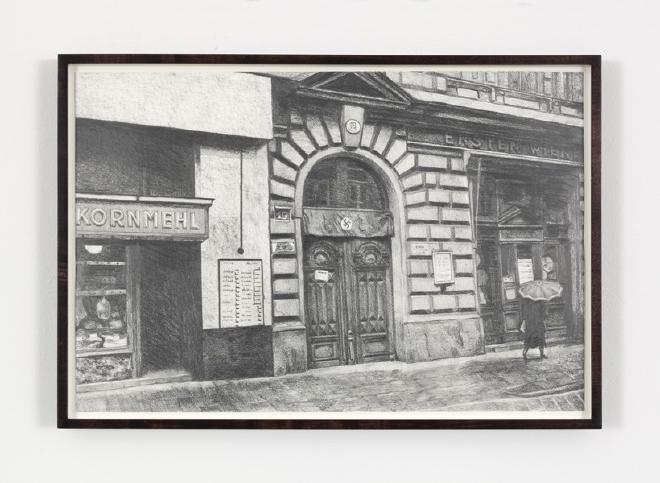

Graphite on paper

Overall dimensions: 45.25″ × 72.5″

Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photo: Steven Probert.

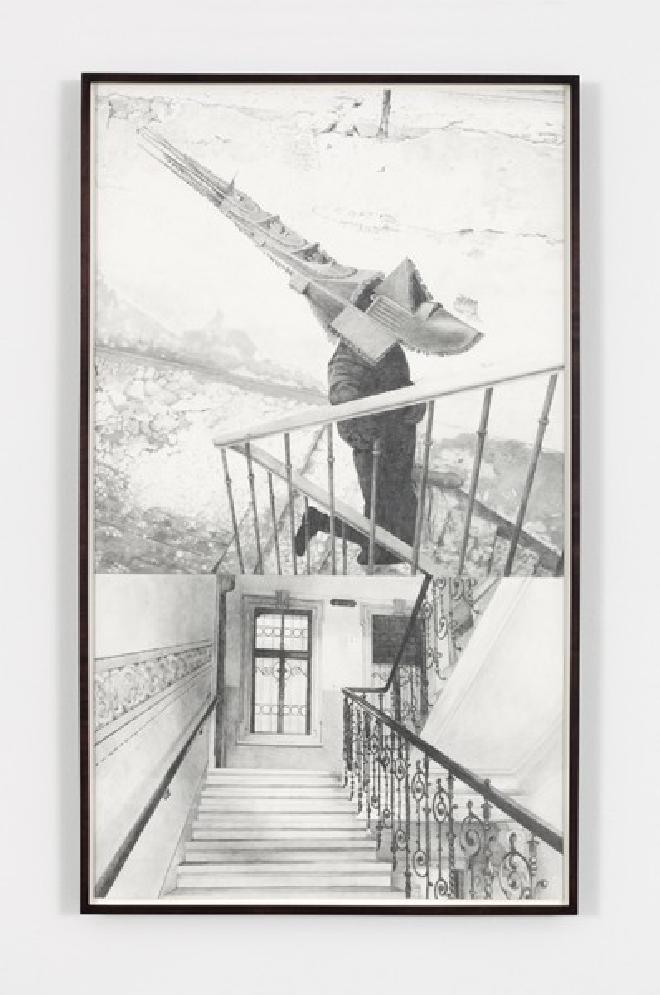

Graphite on paper

38 5/8″ × 54 3/8″

Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photo: Steven Probert.

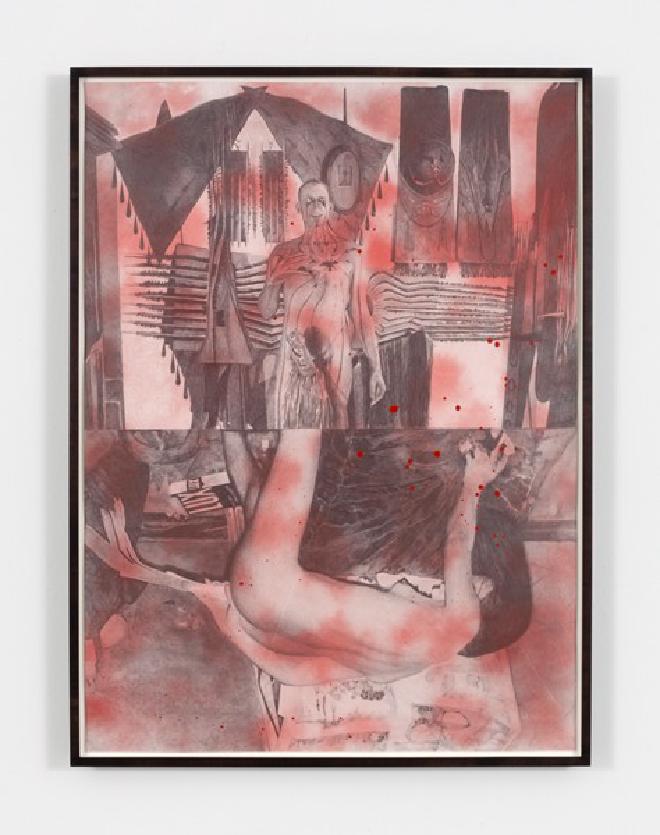

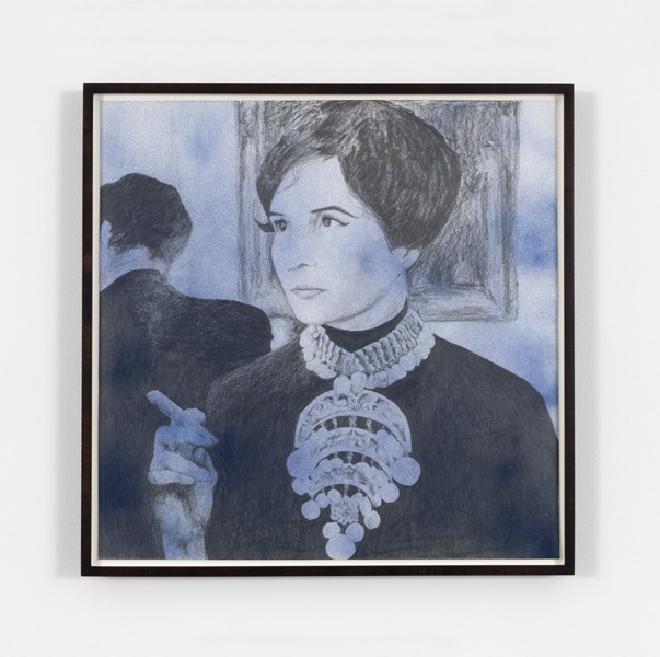

Colored pencil and graphite on paper

Overall dimensions: 26.69″ × 145.75″

Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photo: Steven Probert.

Found objects, light bulbs, plaster, wood, marble, steel, wood, MDF, acrylic, gauche

Overall dimensions: 65.5″ × 56.5″ × 57″

Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photo: Steven Probert.

Found objects, light bulbs, plaster, wood, marble, steel, wood, MDF, acrylic, gauche

Overall dimensions: 65.5″ × 56.5″ × 57″

Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photo: Steven Probert.

Found objects, light bulbs, plaster, wood, marble, steel, wood, MDF, acrylic, gauche

Overall dimensions: 65.5″ × 56.5″ × 57″

Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photo: Steven Probert.

Found objects, light bulbs, plaster, wood, marble, steel, wood, MDF, acrylic, gauche

Overall dimensions: 65.5″ × 56.5″ × 57″

Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photo: Steven Probert.

Found objects, light bulbs, plaster, wood, marble, steel, wood, MDF, acrylic, gauche

Overall dimensions: 65.5″ × 56.5″ × 57″

Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photo: Steven Probert.

Found objects, light bulbs, plaster, wood, marble, steel, wood, MDF, acrylic, gauche

Overall dimensions: 65.5″ × 56.5″ × 57″

Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photo: Steven Probert.

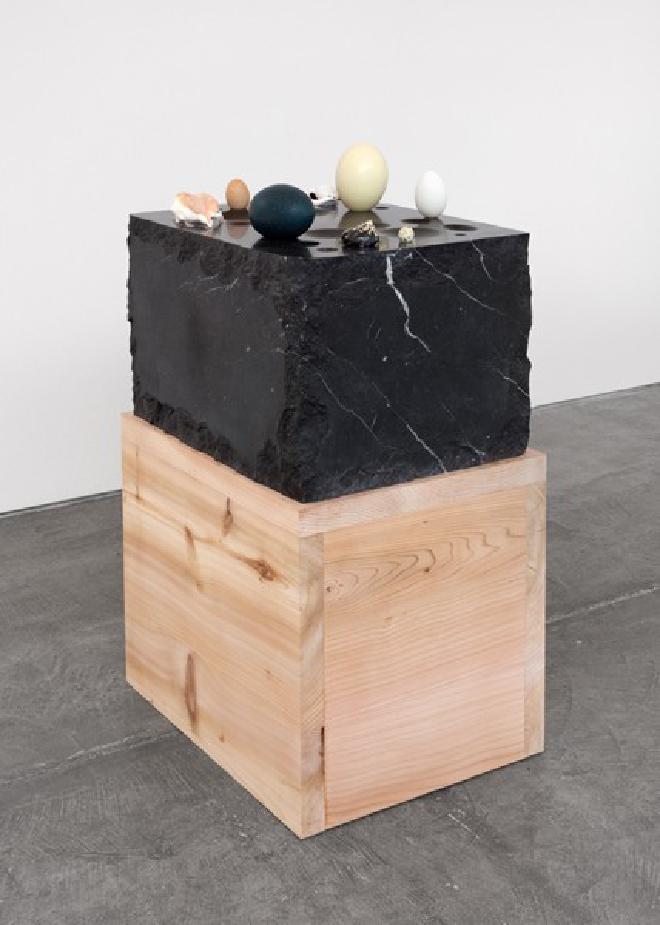

Marble, wood, eggs, shells

Overall dimensions: 34″ × 18.5″ × 24″

Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photo: Steven Probert.

Marble, wood, eggs, shells

Overall dimensions: 34″ × 18.5″ × 24″

Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photo: Steven Probert.

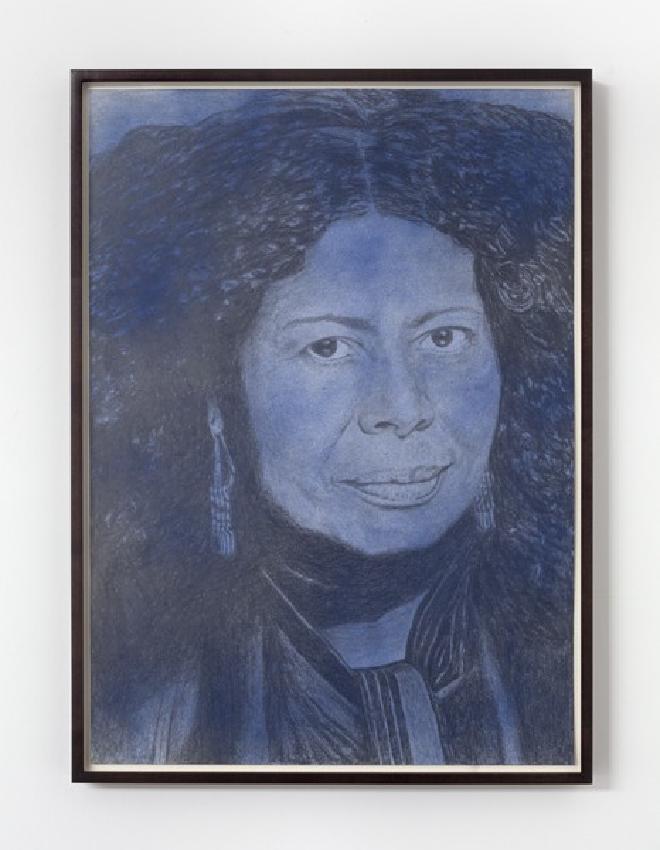

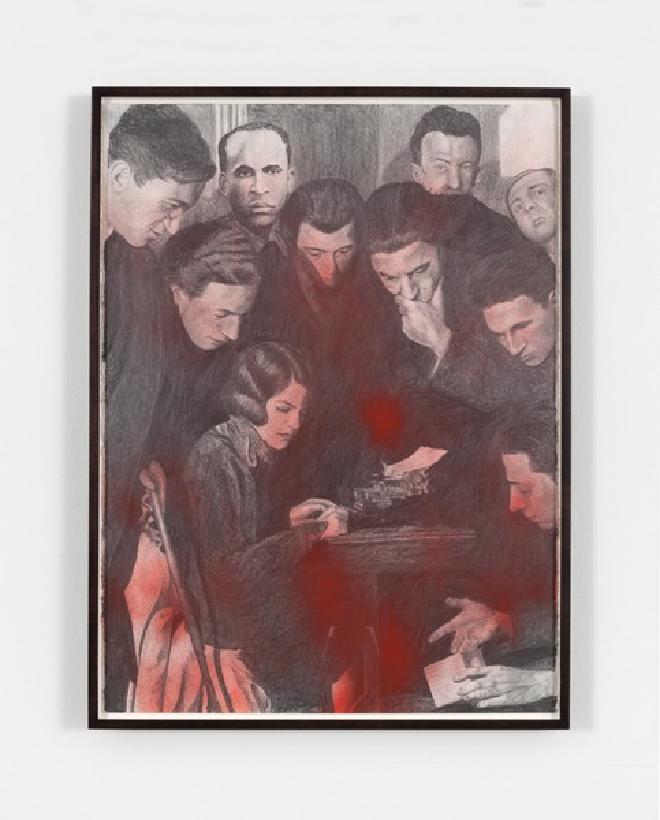

Graphite and acrylic on paper

30″ × 21.5″

Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photo: Steven Probert.

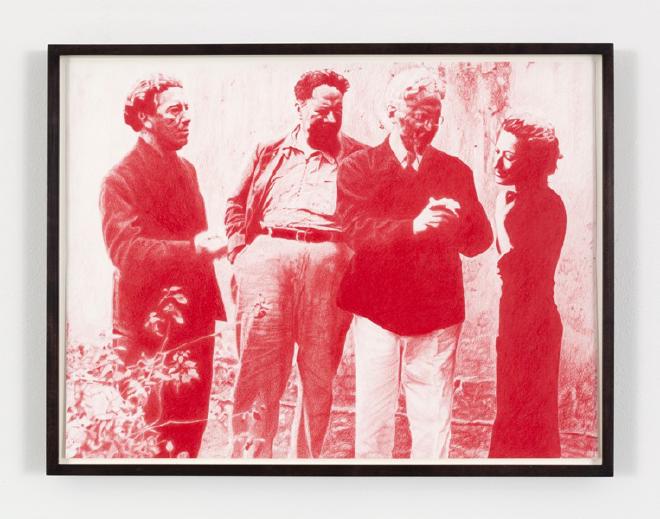

Colored pencil on paper

17.19″ × 23.13″

Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photo: Steven Probert.

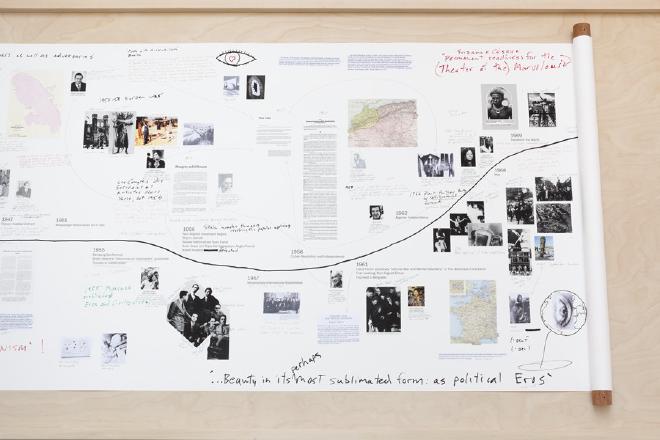

Archival digital printing, collage, graphite, color pencil and ink on paper, African Mahogany

170″ × 35″ × 1.75″

Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photo: Steven Probert.

Archival digital printing, collage, graphite, color pencil and ink on paper, African Mahogany

170″ × 35″ × 1.75″

Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photo: Steven Probert.

Graphite on paper

16.875″ × 24.562″

Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photo: Steven Probert.

Powder coated steel, wood, artillery shell casings, stainless steel cable

55″ × 49.63″ × 41.25″

Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photo: Steven Probert.

Graphite on paper

43.125″ × 25″

Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photo: Steven Probert.

Graphite and enamel on paper

44″ × 32.25″;

Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photo: Steven Probert.

Graphite on paper

26″ × 40″

Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photo: Steven Probert.

, 2014

Graphite and enamel on paper

28.75" × 22.125″

Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photo: Steven Probert.

“)

Graphite and enamel on pape

21.625″ × 21.75″

Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photo: Steven Probert.

Graphite and acrylic on paper

25.75″ × 36.25″

Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photo: Steven Probert.

Graphite on and enamel on paper

30″ × 22″

Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photo: Steven Probert.

Graphite on paper

26″ × 40″

Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photo: Steven Probert.

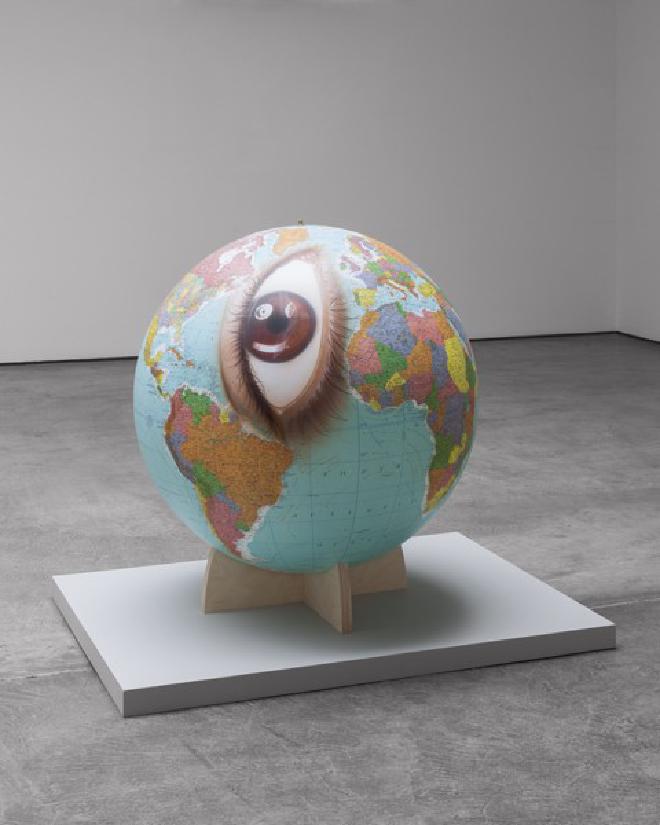

Globe, acrylic

32″ dia.

Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photo: Steven Probert.

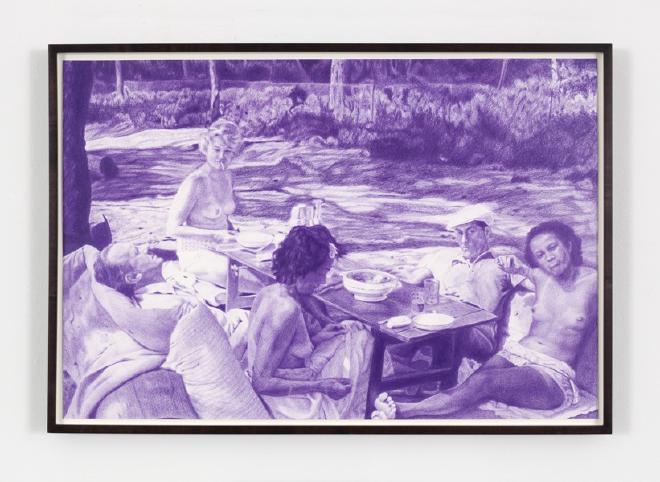

Colored Pencil on paper

20.125″ × 30″

Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photo: Steven Probert.

Colored Pencil and ink on paper

55.187″ × 51.25″

Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photo: Steven Probert.

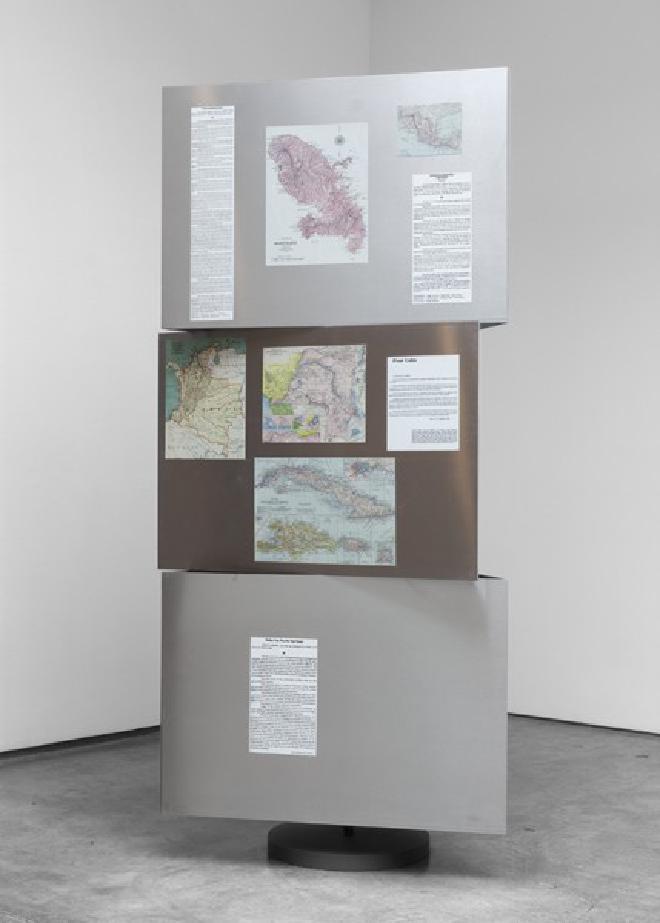

Aluminum, ink on paper

77.25″ × 39.5“ × 39.5″

Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photo: Steven Probert.

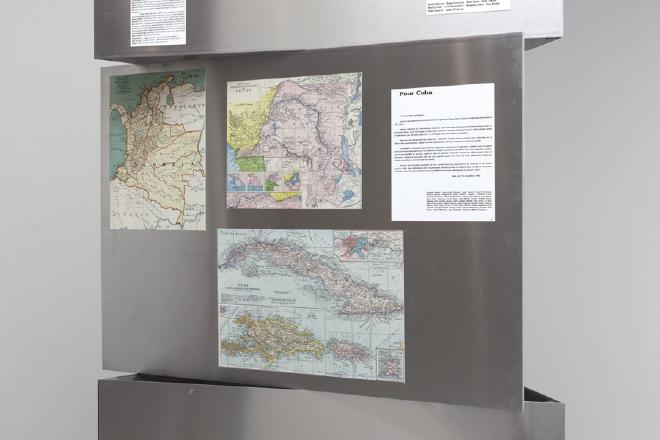

Aluminum, ink on paper

77.25″ × 39.5“ × 39.5″

Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photo: Steven Probert

Text #

Invisible Surrealists is a reimagined history of surrealism. It takes the form of an exhibition that brings writers and artists from the Francophone colonial world into the well-known Parisian narrative. It is a decolonizing project. Surrealism is arguably the most popularly known art movement of the 20th century. In American culture it has become a cliché, overflowing with facile imitations of Salvador Dali and Yves Tanguy, from undergraduate painting classrooms to thrift shops. While academic art history has made the movement canonical, it has framed it in a narrow way, with some notable exceptions. The Eurocentric history has largely excluded the multitudes of writers and artists from the “third world”, the “global south”, from the francophone former colonial world. The established narrative has detached surrealism of much of its radical potential, its capacities for re-imagining social relations, sexual and gender liberation and its commitment to revolutionary political struggles, anti-nationalism and de-colonization.

The central focus of Invisible Surrealists is to re-integrate lesser-known surrealists from the Francophone colonies in the Caribbean, Africa and Asia with the Paris based founders of the movement. Several drawings depict iconic group images of the well-known figures around Andre Breton into which I have added a number of “third world” surrealists. The non-white surrealists who figuratively “join the club” in these works include Aimé and Suzanne Césaire, Jules Monnerot, Rene Menil, Wilfredo Lam and Joyce Mansour among others.

Several works deal with the relationship between war (the European wars, imperialist violence and anti-colonial struggle) and art, between Eros and Thanatos, exemplified by the parallel phenomena of shell shock and the avant-garde “shock of the new”. The First World War also gave rise to the phenomena of “Trench Art”. Soldiers stuck in battlefield trenches for weeks and months on end in hellish conditions began to repurpose the war material around them into things like ashtrays, vases, toys, lighters. Trench art can be understood as a form of sublimation, the soldiers channeling their unconscious aggressive energy toward socially acceptable production. In this way art itself might be understood as a threat to the state of war.

Surrealism opened the door for desire, sexuality and transgression to operate more freely, out in the open, as an alternative to repressive status quo “reality”. Philosopher Herbert Marcuse saw in surrealism the possibility for individual transformation. He theorized that only transformed individuals could make a revolution of more liberatory forms of social relations, and not simply the replacement of one oppressive system by another.

In 1914 the First World War brought home to Europe the reality that civilization and barbarism are two sides of the same coin. The people living under European colonial rule, however, had been well aware of this duality, having lived with the effects, both physical and mental, of its brutality for centuries. Martiniquean surrealist Aimé Césaire wrote simply “Europe is indefensible”. his Discourse on Colonialism, a forceful exposition on the violence of European imperialism. The Parisian surrealists were of course linked with the communist party, largely through Picasso. What is perhaps lesser known is their early break with the CP and their solidarity with anti-colonial struggles around the world. Some of my sculptures and drawings show reprints of several of the anti-colonial tracts that surrealists published against imperialist aggression from Vietnam to the Soviet crushing of Hungarian democracy to Cuba. Many of these texts were composed by the surrealists from the margins and joined by those in Paris.

My project seeks to show that the surrealist ideals of personal, political and social emancipation and transformation should include both the center and the margin in a complex, hybrid arena defined by hues and shades rather than black and white.